Grace Tan wakes up in her neatly kept three-room flat on a quiet Sunday morning. At 34, she’s one of a growing number of Singaporeans living alone.

After a quick breakfast, Grace heads to a nearby cafe in Tiong Bahru with a book. As she sips her kopi, she scrolls through her phone, seeing photos of former classmates with their newborns and toddlers. There’s a tinge of wistfulness, but also contentment. Grace is single by circumstance and choice—no life partner yet, but a life she enjoys. She has a successful career in marketing, freedom to travel, and a close circle of friends. Still, the questions from relatives at Chinese New Year dinners linger in her mind: “Why no boyfriend? Don’t wait too long, ah.” She forces a polite smile whenever Aunties nag her about settling down.

In the solitude of the cafe, Grace ponders how different her path is from what her parents’ generation imagined, and how common her story has quietly become.

Singlehood on the Rise: The Statistics

Grace’s situation is far from unique. In fact, Singapore’s singlehood rates have been steadily climbing for young adults. Data from the Department of Statistics’ 2020 census reveals that the proportion of singles rose across all age groups in the past decade.

The increase was most dramatic for those in their late 20s and early 30s. Among men aged 25–29, the share who were single jumped from about 75% in 2010 to 81.6% in 2020, and for women of the same age it surged from 54% to 69%.

Even in the 30–34 age bracket, singlehood became more common: 41.9% of men and 32.8% of women in that age group were unmarried in 2020, up significantly from a decade earlier. In other words, roughly two in five men and one in three women in their early thirties are now single – a marked shift from previous generations.

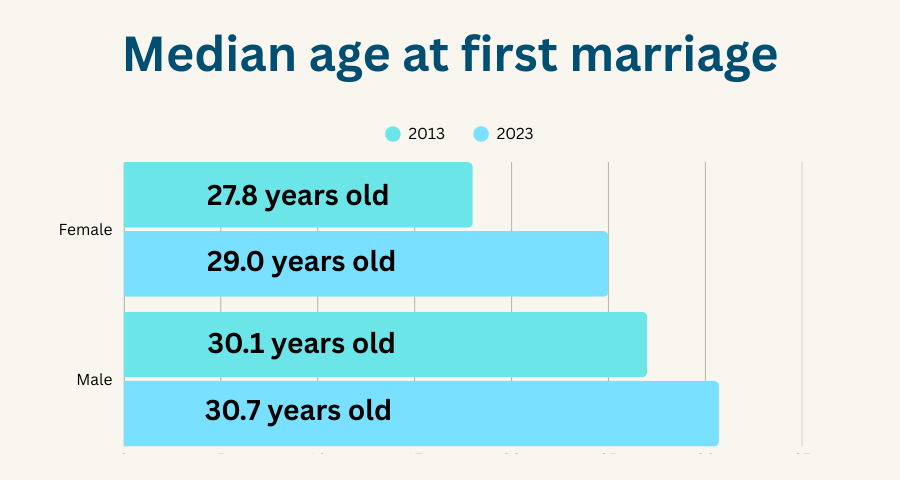

These numbers reflect a broader trend of later marriages in Singapore. The median age at first marriage has crept upward, reaching about 30.7 years for grooms and 29.0 for brides in 2023, compared to 30.1 and 27.8 a decade prior.

Many Singaporeans are simply taking more time before saying “I do.” Some never do at all. Yet interestingly, the overall percentage of singles among the adult resident population (aged 15 and above) actually dipped slightly from 32.2% in 2010 to 31.5% in 2020.

This seeming contradiction is explained by the ageing population – older cohorts in Singapore have relatively fewer singles (many married in their youth), so as the population greys, the total proportion of never-married individuals remains moderate. The real story, however, lies in the generational shift: young Singaporeans today are far more likely to be single than their parents or grandparents were at the same age.

Gender differences also emerge in these trends. Men have generally been more likely to stay single into their 30s than women, as seen in the higher singlehood rates for males in the 25–34 range. Part of this gap closes at older ages, but a legacy of traditional pairing preferences still plays a role. The 2020 census found that singlehood was most prevalent among lower-educated men and higher-educated women.

For instance, over 21% of men aged 40–49 without secondary education were single, versus only 12.3% of university-educated men in that age group. Conversely, highly educated women were more likely to remain unmarried (18.7% of female university grads 40–49 were single, compared to 8.7% of those with below secondary education).

This suggests a nuanced social dynamic: educated women often delay or forego marriage, while less-educated men may struggle to marry, possibly due to mismatches in expectations or economic stability. Such statistics underscore that singlehood in Singapore isn’t a monolithic trend – it varies by gender, education, and other factors.

Behind the Trend: Culture and Economics

What’s driving this quiet rise of singlehood? The reasons are a blend of cultural shifts, economic considerations, and personal aspirations. One major factor is the emphasis on education and career in modern Singapore. Young people often spend their 20s pursuing degrees, building careers, and achieving financial security. Marriage is no longer seen as a must-do by one’s mid-20s; instead, it’s commonly postponed.

As Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office Indranee Rajah noted in 2021, many Singaporeans are deferring marriage or parenthood to focus on their careers.

This focus on personal development means that relationships and family-building happen later, if at all. By the time individuals feel “ready” – having secured a good job, savings, maybe a house – they are often in their 30s, and some find it challenging to meet a suitable partner by then.

Economic pressures also loom large. The cost of living in Singapore is high, and raising children is an expensive endeavor. High childcare costs, housing prices, and the pressure to provide the best for one’s kids can make young adults hesitant to marry and start a family early. Ms Indranee Rajah highlighted that the financial cost of raising children is frequently cited as a reason for the low birth rate.

It stands to reason that the same cost concerns can delay marriages – couples (or singles contemplating marriage) want to be financially prepared before tying the knot. Additionally, today’s young adults have grown up in an era of greater individualism and lifestyle aspirations. Many want to enjoy personal freedom, travel, hobbies, and even entrepreneurship, without the traditional rush to settle down. The cultural narrative has gradually shifted from “marry young and start a family” to “find yourself and your stability first.”

Furthermore, attitudes toward being single have softened compared to the past. There is less stigma now in remaining unmarried through one’s 30s; in some circles it’s even seen as a positive choice for those who value independence. Women, in particular, face more accepting attitudes in pursuing higher education and leadership roles at work, even if that means postponing marriage. In earlier generations, a woman unmarried by 30 might have drawn pitying clucks about being a “spinster.”

Today, a 30-something single woman like Grace is likely to be admired for her career achievements and active social life. Of course, underlying cultural expectations haven’t vanished entirely – family elders still drop pointed reminders about biological clocks and the joys of grandkids. But by and large, there’s a growing understanding that marriage is not the only path to a fulfilling life. The government’s own surveys show that the majority of young singles do still desire marriage and parenthood eventually (about 8 in 10, according to a 2021 poll), yet the timeline and priorities have clearly changed.

Housing Hurdles for Singles

One uniquely Singaporean factor entwined with marriage decisions is housing policy. In Singapore, access to affordable public housing from the Housing & Development Board (HDB) is tightly linked to marital status. The system has long incentivised getting married by offering generous housing grants and options to young couples, while singles historically had to wait and face restrictions.

Grace knows this all too well. In her late 20s, as friends applied for Build-To-Order flats (new HDB apartments) with their fiancés, she had no such luck as a single. HDB rules stipulate that unmarried individuals under 35 are ineligible to buy subsidised flats on their own. Only at age 35 can singles purchase a flat independently, and even then, until recently they were limited to smaller units (typically two-room flats in non-mature estates) if buying new from HDB. The intent behind these rules is explicit: by tying housing to matrimony, the policy aims to encourage family formation – essentially nudging citizens to marry and have children in order to secure a home.

While well-intentioned in bolstering traditional family units, these housing hurdles have made life challenging for singles. Those like Grace who didn’t marry by their early 30s often end up either living with parents longer than they’d prefer or renting on the open market (an expensive prospect in Singapore). Some, like a marketing professional named Fadhil Azmi, resorted to renting for years; he rented a room for a decade until he finally turned 35 and became eligible to purchase an HDB flat of his own.

“The amount I spent on rent in the last 10 years, I could have paid for the house back then… I would have been debt-free by now,” Fadhil lamented of the policy that kept him from buying earlier.

There have been gradual changes to acknowledge these realities. Over the years, HDB has slowly relaxed rules: since 2013, singles above 35 can apply for new two-room flats (a step up from the earlier rule of resale-only). There are also special considerations now for single unwed parents and divorcees, who previously fell through the cracks of eligibility. In 2023, authorities even piloted a scheme allowing low-income singles to rent public flats alone (previously they had to pair up with another single under the Joint Singles Scheme). These tweaks suggest a recognition that the social landscape is changing – not everyone will form a nuclear family, and those who don’t still need a place to call home.

Yet, many singles feel the policies haven’t caught up with the times. There remains a sentiment that the system heavily favours married couples, leaving singles as an afterthought.

As one 31-year-old single Singaporean, Abhishek, shared in an interview, the messaging can sting: “At the end of the day, if your objective is just to give birth and have babies, perhaps we don’t fit in the country… What kind of message are you sending to people who don’t conform to that?”. His words underline a palpable concern – that lifelong singles or those who choose different paths may feel marginalised in a society built around family norms. Balancing housing supply and national goals with inclusivity for diverse household types is a challenge that Singapore is still navigating.

Falling Birth Rates and a Greying Society

One direct consequence of more people marrying late or never marrying is fewer babies being born. Singapore’s total fertility rate (TFR) – the average number of children a woman would bear in her lifetime – has been on a persistent decline, hitting historic lows.

By 2023, the resident TFR had fallen to 0.97, dropping below the psychologically significant threshold of 1.0 for the first time. This is less than half the replacement rate of 2.1 needed for a stable population, and among the lowest fertility rates in the world. The trend is closely linked to the marriage patterns: when people marry later or stay single, naturally there is less time and opportunity to have children (if they intend to at all). It’s not the only factor – even married couples are having fewer kids on average, influenced by the same cost and career considerations discussed earlier – but the rise of singlehood is a major piece of Singapore’s “great baby drought.”

The government is acutely aware of these demographic challenges. Ms Indranee Rajah, who oversees population matters, has pointed out that Singapore’s low fertility mirrors trends in other advanced societies where individual priorities have shifted.

Young adults now cite multiple reasons for delaying or avoiding parenthood: high financial costs, the pressures of parenting in a competitive environment, difficulties balancing work and family, and a desire for personal time even after marriage. Add to that the fact that some never find the right partner, and it becomes clear why the stork is visiting ever less frequently.

The implications for society are profound. Singapore is ageing rapidly. In 2020, about 15% of residents were 65 or older, up from just 9% in 2010 – and that proportion is projected to rise to roughly 25% by 2030. With more seniors and fewer young people, there will be greater strain on healthcare and pension systems, and a smaller base of working-age citizens to support the elderly.

A greying population could also slow economic growth and dynamism, as the workforce shrinks relative to total population. Social infrastructure will need to adapt: for example, there may be more demand for assisted living facilities, medical care for age-related illnesses, and community support networks for older folks living alone.

Indeed, as singlehood becomes more common, Singapore might see more elderly people ageing alone, without immediate family caregivers. This raises concerns about loneliness and care for the aged. Community programs and social services may have to step up in filling the gaps that adult children traditionally played in caring for ageing parents.

The government has started various initiatives – from active ageing centres to healthcare subsidies – to brace for this future. Policies encouraging marriage and parenthood (such as baby bonuses, parental leave, and housing perks) are continually being enhanced, but the effects of those are yet to reverse the demographic tide. The “quiet rise” of singlehood, if it continues, means Singaporean society will need to reimagine support systems in everything from housing to eldercare to ensure that no one is left behind, married or not.

Loneliness, Freedom, and Changing Attitudes

What does this shift mean for the individuals living solo – emotionally and socially? The experiences of singles like Grace are diverse. On one hand, there is a newfound sense of freedom and self-determination. Many single Singaporeans embrace the chance to develop their identities, careers, and passions without the immediate responsibilities of spouse and children.

They often form strong friendships that become like “urban families,” supporting each other’s dreams. Grace, for example, enjoys the freedom of deciding how to spend her time and money – she can enrol in night classes, devote weekends to volunteering, or splurge on a solo trip to Japan without needing to consult a partner. There is a quiet contentment in crafting a life on one’s own terms. For some, singlehood is not a sad singleton status at all, but a deliberate choice for independence.

Yet, the single life can also come with emotional challenges, chiefly loneliness and societal stigma. Human beings are social creatures, and going through life without a long-term companion or immediate family of one’s own can at times feel isolating. A recent poll by the Institute of Policy Studies found that young Singaporeans (aged 21 to 34) reported the highest levels of loneliness and social isolation among different age groups.

In the survey, nearly 60% of youths in that age range considered themselves lonely, and 15% said they had nobody to turn to when facing important difficulties. It’s telling that this age bracket overlaps with the period many remain single. The late 20s and early 30s can be a paradoxical time – while one might be surrounded by colleagues and friends, it’s also when peers start coupling up and “peeling off” into their married lives. A single person can suddenly find their social circle shrinking or changing, leading to an acute sense of being left behind.

Embracing a New Normal

As the afternoon sun casts dappled shadows on the cafe table, Grace closes her book and reflects on her day. She’ll be meeting a few close friends (two married, one single) for dinner later – a tradition they’ve kept since university. Her life may not follow the traditional template of marriage-then-children, but it is hers, and it is full in its own way. The rise of singlehood in Singapore is, in many ways, the story of individual journeys like Grace’s quietly reshaping society.

Participants at a masked speed-dating event for singles in 2016. Such events were designed to help self-conscious singles step out of their comfort zone. As more Singaporeans remain single longer, social activities and support networks for singles have grown, reflecting a gradual normalization of solo living.

Sources: Department of Statistics Singapore; Census of Population 2020; Ministry of National Development; Today news reports; Channel NewsAsia; National Population and Talent Division; Institute of Policy Studies.